Inspired much by the success of companies like Snowflake, Observe Inc. set out to build a usage based pricing model. I’ve learned a ton from this process and continue to do so each week. This blog series will catalog our journey and things I wish we had known on day 1. It’s broken up into 3 parts:

- Why Usage Based Pricing?

- How you implement it

- Its challenges

Part 1 - Why Usage-Based Pricing

Aligned incentives are the end of shelfware

“Shelfware” is a meme that’s plagued enterprise software since its incarnation. It’s a dark secret that lots of software never gets deployed. In the world of on-premise software licenses, it’s not uncommon for licenses to get thrown in as part of a larger deal. The root of this problem is misaligned incentives. For example, imagine retail software that charges by brick and mortar location. That company is going to get paid irrespective of how much each store really takes advantage of said software. In their eyes simply deploying it to a store means they are going to get paid. It doesn’t matter if anyone actually uses it.

In the world of usage-based pricing, the customer and vendor incentives are aligned. If a customer does not use the software, the vendor will not make any money. They are incentivized to build software their customers will actually use. However, based on consumption patterns we’ve seen that vendors are also incentivized to improve value to encourage usage (more on that shortly).

Newfound Elasticity

Every shift in computer infrastructure has been accompanied by a correlating pricing model. Let’s look at the evolution of software pricing.

Perpetual Licensing

When the only way to run software was to buy the servers it ran on, it made sense to treat software like hardware as a Capital Expenditure. Customers would buy a version of said software with a big principal outlay in the first year, then pay 10-20% of that cost each year for maintenance and support. Usually, four years in a “refresh” would happen due to a newer version or a change in the license. This is when the dreadful software license audit would take place and coincided with a datacenter infrastructure overhaul.

Subscription

A myriad of trends made it economical and acceptable to purchase software as a managed service. Salesforce was one of the original kings of this — by getting in the door with a single salesperson and charging per user. Subscription software usually starts out cheaper than purchasing a pereptual license but can get out of control over time as consumption of the software increases. Given the opaqueness of the unit (i.e. user, server, GB ingested, API calls, etc ) and the need of the vendor to cover fixed costs, it’s difficult to optimize.

Usage

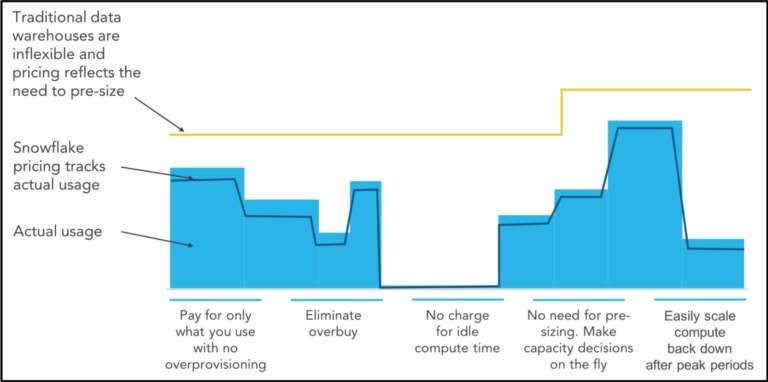

Something changed profoundly with the advent of the cloud — suddenly every company had unlimited compute resources. Even better, they only need to pay when they are using those resources. With that constraint removed software engineers can now build software that is elastic. It’s simple — you charge customers only when they use the system. When they aren’t using the system you don’t need to bill them because there is no cost to you. All of this is possible so long as you build software that can take advantage of the elasticity of the cloud.

*Credit - How Usage-Based Pricing Delivers a Budget-Friendly Cloud Data Warehouse

Jevons Paradox

On March 2nd, Snowflake held their earnings call and their stock fell 25% in after-hours wiping out billions in market capitalization. Why did they get dinged so badly while growing at 102% at $359.6 million? Because they decided to pass on efficiency tweaks to their customers sacrificing short-term growth. As Eric J. Savitz of Barron’s commented on the earnings, “CEO Frank Slootman explained in an interview that the company made a tweak to its software in January that allows customers to do the same work with fewer resources.”

This is a bet on something called Jevons Paradox:

“Morgan Stanley analyst Keith Weiss said in a research note that Snowflake is banking on a theory called Jevons’ Paradox, named for the 19th century English economist William Stanley Jevons. The idea is that as technological progress increases the efficiency with which a resource is used, the rate of consumption rises due to increasing demand.” - Snowflake Stock Falls as a Software Tweak Hits Revenue. Analysts Remain Bullish.

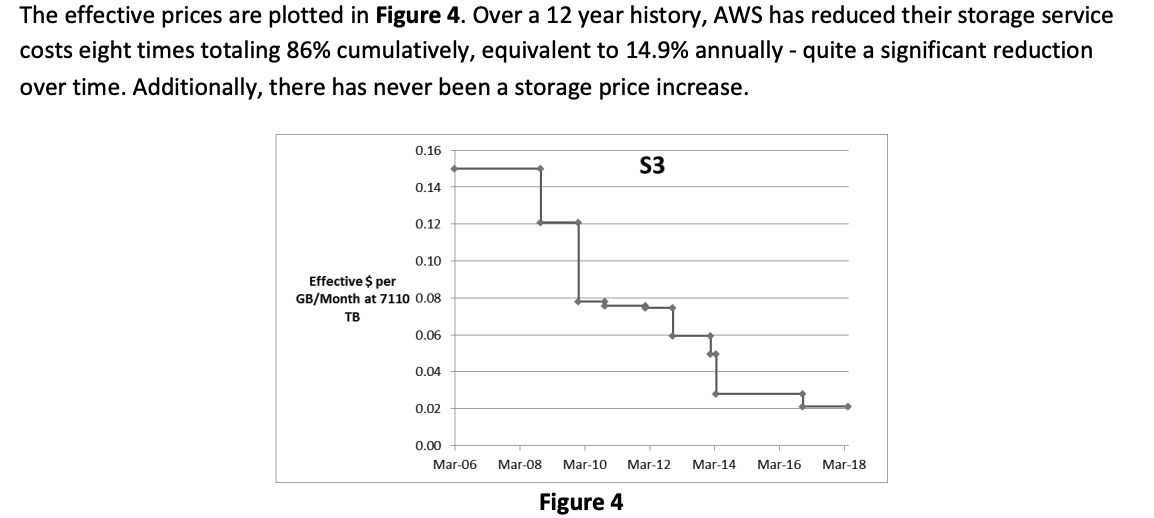

If that sounds crazy to you look no further than Amazon Web Services, which is notorious for accounting price decreases. This report from the NRO and CAAG outlines the cost decreases for storage on AWS:

*Credit - Forecasting Future Amazon Web Services Pricing

*Credit - Forecasting Future Amazon Web Services Pricing

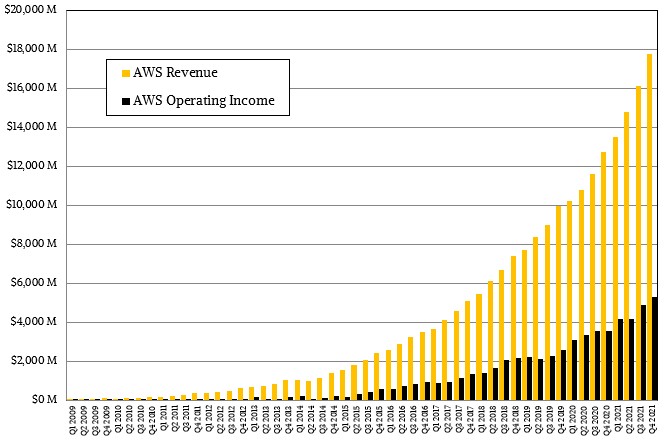

If you think it’s crazy to decrease the price of a service in the hopes of making more money take a look at the revenue growth of AWS. Last year they grew revenues 39.5% to $17.78 billion. That kind of growth is almost unprecedented in the computer infrastructure business.

Usage-based pricing lets you take advantage of this paradox.

*Credit - *MILLIONS PAY AWS TO GIVE AMAZON AN INSURMOUNTABLE IT ADVANTAGE

‘Til next time

In part 2 I’m going to cover how to actually implement usage-based pricing. If you choose to go down this path a lot of technical and process work lies ahead.